Table of Contents

Each teacher always does their best to plan engaging, educational, and well planned lessons for their students, but oftentimes the focus on planning is on how much time is available and what content needs to be gotten through in order to have a full course. Rather than schools focusing on curriculum, schools should focus on student needs. Students need a brain based lesson plan that teaches the way that the brain learns naturally.

This professional development activity will guide teachers on another way to think about building their lesson plans that is based on how the brain works rather than how to fit a curriculum into the number of class blocks allotted for the year. While it is important to be mindful of time used, when focus is put on cramming the proper quantity of content into a block as possible, the quality of the time students spend developing how to use what they learn is severely limited.

Questions to Consider on Lesson Planning

Discuss with a table partner, or do a brainstorm if working alone, what steps you go through to develop a lesson plan. What do you start with? What is your thought process? Discuss any differences between group members, or if brainstorming alone, between how you used to work vs currently plan.

Research Based Tips for a Brain Based Lesson Plan

Before getting started, here are a few key things to keep in mind when planning any lesson or activity. These are the foundation to any brain based lesson plan and will need to be mindfully implemented to have a solid foundation to build your class activities on.

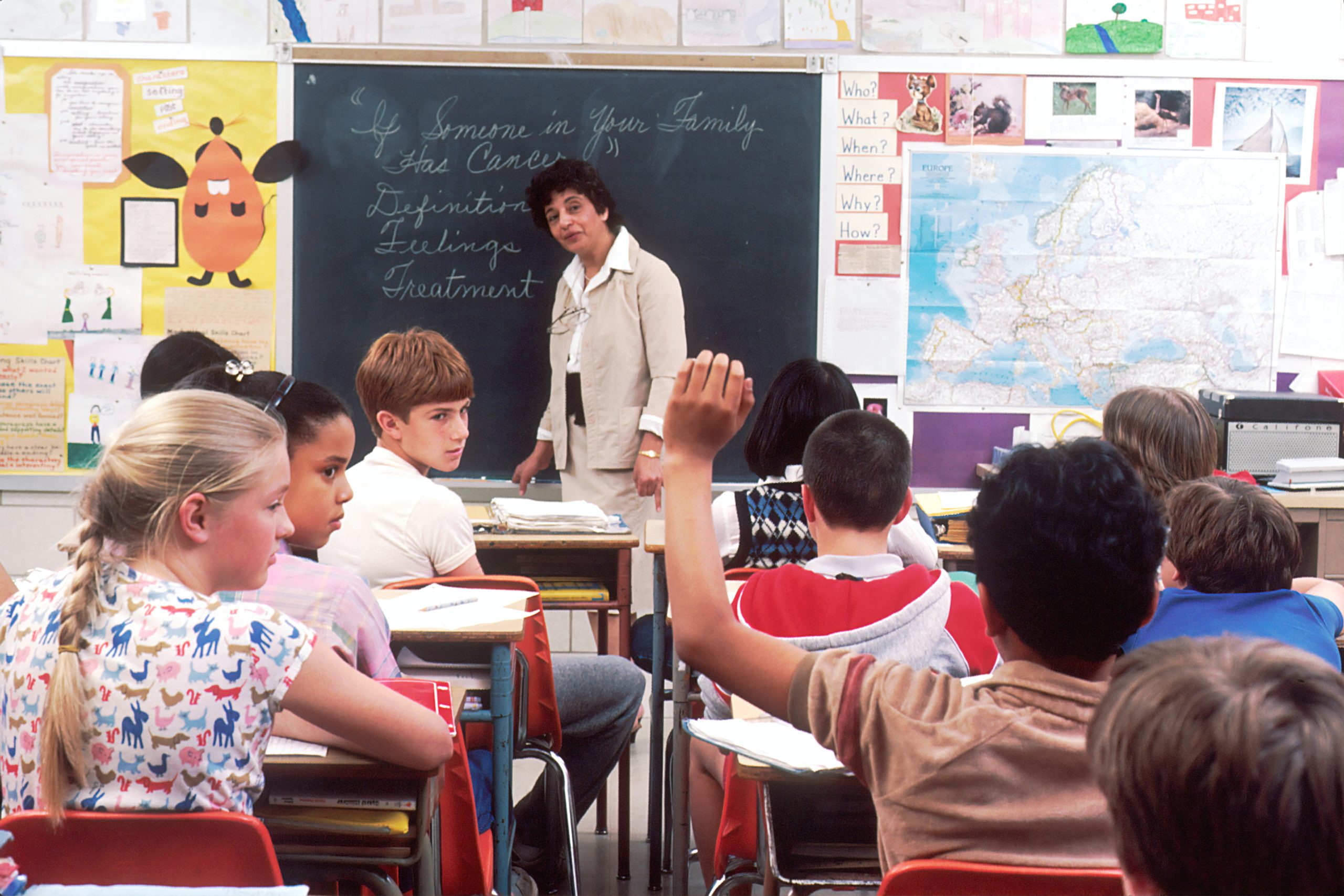

1: Give instruction time a time limit.

Student attention is a teacher’s most precious resource. While research is very conflicted on exactly how much time a teacher has with their students’ full attention, the evidence is clear that even the strongest students will have lost some amount of their ability to pay attention by the fifteen minute mark. (Bradbury)

There are a myriad of factors that can affect how long a student’s attention is held, but one that is easy for any teacher to control is how far into the class period the lecture is placed.

Research showed that attention is best at the beginning of class, and that even when refocused, students lose attention more and more quickly as the class period progresses. (Bunce et al.) Teachers should schedule and plan their lectures carefully and place them as early as possible in their class periods.

It is also important to remember that question and answer time also requires students to remain focused on a single speaker, and so this time should also be accounted for in planning lectures. Teachers always expect students’ presentations to be timely and well organized, and they should have the same expectations for their own lectures.

Write the instructions clearly on the board before class, set the class up for success with a brief lecture, a few questions, and then allow the students to get to work. This will be the most efficient use of attentional resources and so is key for any brain based lesson plan.

2: Activate multiple senses. Don’t just talk or read about something.

It is very important to not just talk or read about a topic, but to see it in action, and if possible to work with it in a physical context. This focus on multiple sensory systems creates a stronger memory trace in whatever is being learned by having input from two separate pathways in the brain.

When a part of the brain receives input, it strengthens its connections there. Including pictures, videos, simulations, games, and even hands on projects when financially possible helps students to engage more of their brain and create a better network of understanding around a subject.

A common saying in neuroscience is that “neurons that fire together wire together” meaning that when sensory pathways are mindfully connected, both pathways can be activated with either route of entry. If students experience a subject with multiple sensory systems, those experiences will connect together in the students’ brains.

Because of this, they will have a fuller mental impression and a more complex understanding of how that topic works in multiple contexts. Instead of just talking about the bones of the body and the joints that connect them, having students actually locate and touch or use that part of their body when learning about it will help them to literally feel how joints and bones work together and connect what they’re learning to their own bodies.

This will make it easier for students to understand the practical aspects of a course even when they are just reading or hearing about it during a later lecture. Because the teacher has mindfully connected how those concepts apply in another sensory context, it will be easier for students to conjure up those past experiences and know why they are significant or perhaps nonsensical.

In a history class, rather than just reading about a time period, watching films or viewing historical simulations will help students to understand the context of the historical events in addition to now having visual and auditory information connected to the time period. A brain based lesson plan doesn’t just explain something to students, it let’s them see and hear for themselves firsthand whenever possible.

3: Ensure each class builds a practical skill, not just “exposes” students to things.

One of the most commonly missed fundamentals of a brain based lesson plan is the practical context of what is being learned. Research consistently shows that learning is firmly bound to the context in which it is learned. (Brown et al.)

This means that students aren’t good at transferring what they’ve learned into different contexts. Teachers often notice this when they give students a different type of problem that really is just asking the same thing they’ve been teaching all unit, but because it looks significantly different, students will often struggle.

This means that teachers need to plan lessons that teach students information in the contexts that they will need it in the future. No one would expect a medical student to be able to perform a procedure without first performing it themselves.

Certainly, the student would read about the procedure and then watch it performed by an expert before performing it, but most schools still struggle to help their students actually perform classwork in a way that prepares them to use it in professional contexts.

Steps to Create a Brain Based Lesson Plan

Step 1: The Purpose (A practical one!)

The first step of any lesson is to decide what you want students to achieve from the day. While it may seem easy to say something like “Well, my purpose for this lesson is to teach the students about the digestive system” or “That day we will be going over ____” but this isn’t specific enough.

Instead, teachers should strive to think more about what they would like for their students to be able to do rather than what they should know. This approach actually kills two birds with one stone as students will need the knowledge the teacher wants to impart to students in order to be able to complete the tasks assigned.

These skills should be very specific and not general topics or skills like “algebra” or “essay writing”. Instead, very specific purposes such as “students should be able to calculate how to fairly allot a limited resource using percentages.” or “Students should complete one advertisement through their medium of choice using at least three different methods of persuasion.”

Bad examples:

“I want my students to understand fractions”

“On Tuesday we are going over the key turning points of World War II”

“Act III of Macbeth”

Good Examples:

“Students will be able to calculate fractions from two integers and be able to turn that into a percentage in the context of making an imaginary budget.”

“Students will be able to explain some of the causes of warfare and be able to go into detail on a historical context they studied using peer reviewed sources to back up various claims for the cause in their specific context.”

“Students will craft the text of their blog post ensuring it solves a specific reader problem and has a clear target audience through their authorial choices.”

Step 2: The Students (the levels)

After deciding what students will be seeking to achieve during class, the teacher needs to plan is what level of expertise they would like for students to achieve in the task. Teachers will need to consider not only the age of their students, but the amount of background knowledge they have in the subject and what will be expected of them in the following year.

This will also be very individualized for each student in the end as each student has their own propensities and personalities that will help or hinder their ability to perform the skill being taught that day.

One student may be a natural speaker who is confident in front of their peers and so will do well on their speech performance while a shy student may struggle to even give a presentation despite having greater knowledge in the subject. The following day’s writing task might flip this dynamic however, and the shy student may perform better when writing, increasing the expertise the teacher can expect shown from their work.

Best practice here is to have regular conversations between teachers in adjacent grade levels about where the students have come from in their learning and what the next year’s teacher will need students to be able to do in order to have the fundamentals necessary to complete their class activities.

Talking with a previous year’s teacher can be beneficial for seeing what students should already know and limiting the amount of diagnostic testing needed to ascertain student proficiencies. Teachers from previous years can also give insights into the personalities of students and what helps them be successful, however it is important to save these conversations until after the year has gotten started as each student deserves to have a fresh start to the year without preconceived notions about their behavior, good or bad.

After the year is a month or two in, these conversations can be beneficial to see which patterns have continued, which students have seen a drastic change and need follow up, and share student strategies. Conversations with the teachers of the grade above should happen early, however. This will allow teachers to plan lessons with next year’s expectations in mind as early as possible and not feel pressured to shift gears mid year.

Once an appropriate level of expertise has been decided, the teacher needs to create an instruction sheet for the students detailing what is expected for the day’s activity, giving exact numbers when possible, and explaining how best to complete the task and the approximate amount of time each step should take. The teacher should also provide examples of completed projects at various levels of expertise to help students notice what aspects constitute expertise in what they are studying.

While it may be time consuming to always have examples of each activity, research shows that activating a student’s visual systems is key to helping them see how best to do work. (Goldstein et al.) When they can literally see what is expected and their work differs, they are better equipped to see what to do to improve their work.

Step 3: The Activities (including lectures)

The last step is to plan out the timing of the lesson and any necessary pre teaching activities so that student attention levels are considered, and efficiency is maximized for the precious little time teacher and student have together. Activities that might be needed for a student to be able to complete the day’s practical skill might include a brief lecture or a video about the topic to help students get inspired and see why what they will be learning that day will be beneficial for them.

There may also need to be a bit of time going over examples if the teacher feels students won’t be able to identify what skills are being targeted that day, but in general, the teacher should give the vast majority of the rest of class time to letting students work on making the practical application of the skill you’re teaching.

Student attention is a very valuable resource and teachers need to be mindful with how much of class time is taken up with lecturing. Various research into attention suggests a range of time spans that people can hold their attention, but the suggested numbers of between less than one minute to up to 15 minutes often are well under how much time many teachers spend lecturing each day.

Another important consideration is that question and answer time should still be counted in lecture time as all but one student at a time is having to hold their attention on whoever is speaking.

Lectures may be necessary to give students a bit of background, explain terms, or give instructions, but teachers should plan what they are going to say and give it a clear and short time limit including time for questions or class discussion in that time as well.

Additionally, keeping in mind the research discussed above, that attention is highest and able to be held the longest at the beginning of class, lectures should be seen as getting the class started, giving any instructions, but the rest of the class should generally be devoted to letting students work on their task while the teacher floats helping as appropriate. (Bunce et al.)

Students should leave class each day having created something themselves, and not spent the whole class passively listening. While some tasks, especially for older students may include projects that span days or even weeks or more, this is still project based learning and centered on the student leaving the class with not only the knowledge in their head, but a portfolio of practical activities and projects to take with them and build upon in coming years.

Changing from teaching about topics, to guiding students through projects and creating examples and instructions for each might seem like it adds a lot of work to the teacher’s plate, but creating long slide show presentations and having to continually refocus students’ attention to the lecture or discussion is also a lot of work.

Putting the focus of lesson planning time on creating meaningful skills in students not only has the good brain based fundamentals of student centered learning, but also changes the classroom dynamic from students seeing the teacher as someone constantly demanding their attention, so someone who helps them start off their work day and then is there to support them as they do their work. This will help to reduce stress in the classroom as the teacher doesn’t have to constantly fight to be heard, and students don’t have to constantly fight their brains to stay focused.

Next Steps

Now it is time to put what you have learned to practice. Plan an upcoming lesson using the principles you’ve learned from this professional development. Don’t have time to start a new one? Grab an old lesson plan and see how you could improve it using the brain based principles in this guide.

Want more like this? Make Lab to Class a part of your weekly professional development schedule by subscribing to updates below.

References

Bradbury, Neil A. “Attention Span During Lectures: 8 Seconds, 10 Minutes, Or More?”. Advances In Physiology Education, vol 40, no. 4, 2016, pp. 509-513. American Physiological Society, doi:10.1152/advan.00109.2016.

Brown, John Seely et al. “Situated Cognition And The Culture Of Learning”. Educational Researcher, vol 18, no. 1, 1989, pp. 32-42. American Educational Research Association (AERA), doi:10.3102/0013189×018001032.

Bunce, Diane M. et al. “How Long Can Students Pay Attention In Class? A Study Of Student Attention Decline Using Clickers”. Journal Of Chemical Education, vol 87, no. 12, 2010, pp. 1438-1443. American Chemical Society (ACS), doi:10.1021/ed100409p.

Goltstein, Pieter M. et al. “Mouse Visual Cortex Areas Represent Perceptual And Semantic Features Of Learned Visual Categories”. Nature Neuroscience, vol 24, no. 10, 2021, pp. 1441-1451. Springer Science And Business Media LLC, doi:10.1038/s41593-021-00914-5.