Table of Contents

How is teaching older students different from younger students? As the brain matures, the way it processes information changes. Teaching young students differs significantly from teaching high school or even middle school students. As their brains gain more experiences and they test out different learning strategies, certain pathways in their brains will be strengthened and be favored as they process similar information later. This effect is most well known with the concept of preconceived biases, but this isn’t the only way the brain’s ever changing contextual architecture affects a person’s experience of life.

The way teachers present information in their classes will shape how their students approach and feel about it but as students age, the teacher may have to be more flexible in working with the students’ already ingrained differences rather than trying to reshape and mold their students. Both teachers of young and old students have an important task and unique challenges to face when working with their students, but recent research on how aging affects learning in the brain can help teachers and administrators see why approaches may need to be more individualized as students age.

New Research on Differences Between Older and Younger Brains

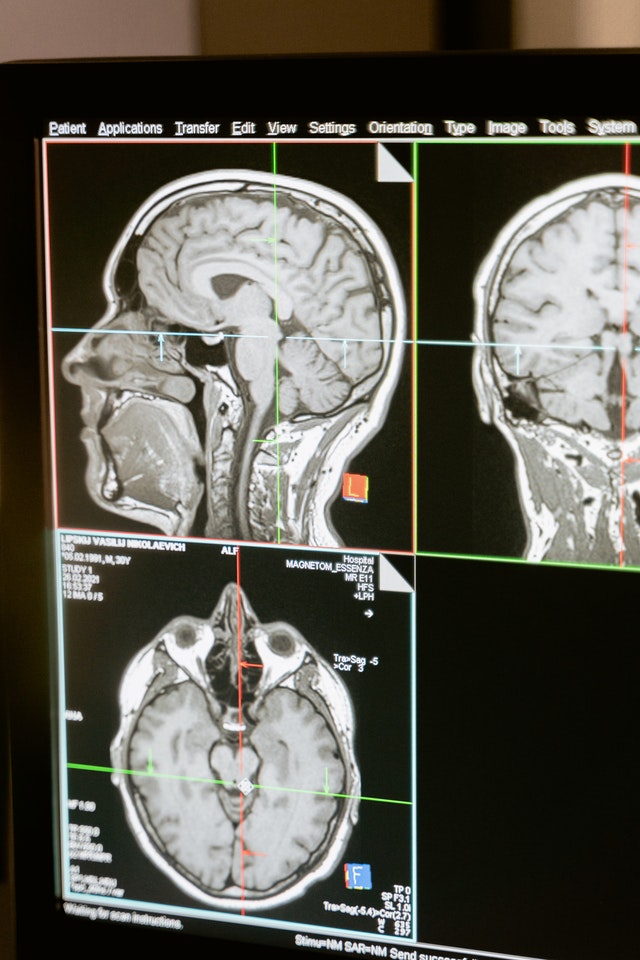

Researchers out of the University of Texas at Austin recently published a paper in Nature on the ways the memory systems of the brain develop as people age. (Schlichting et al.) The researchers had the participants lay down in an MRI machine that would track their brain activity and help the scientists see which areas of the brain were active as the study was conducted. As the patients were being scanned, they were shown a series of images and asked questions that were meant to test their brain’s ability to make inferences based on what it had seen before.

While all participants used their memories to help them answer the questions, the strategies they employed were significantly different as the participants aged. Participants with fully mature memory systems regularly verbalized what they remembered from before when discussing answers.

Adult brains were significantly more adept at actively using connecting memories and making inferences than brains of younger participants. They were able to make multiple connecting memories work together to give a full picture of what they were being asked which helped them make more complicated inferences based on what they had seen previously.

Younger participants also used their memory, but the less mature the memory system was, the less interlinked those memories would be and fewer inferences could be made. For example, if a younger participant was shown an image or a video of a parent bringing a child to school, and then a different parent coming to pick that child up from school, they would be able to remember and link both parents with the child. However, if they were then asked to link various parents together, including the two they had seen bring the child to school, they would be less likely to use that memory of the parents bringing and picking up their child from school to say that they were a couple.

This is because when younger brains with less developed memory systems lay down a new memory trace, it isn’t immediately linked with any other memory traces and works as a stand alone memory. As one of the researchers explains, “In the absence of a mature memory system, the best thing a child can do is lay down accurate, non-overlapping memory traces”.

This is why when asked about either parent individually, they are able to access that memory, but when asked to link those two memories together, they struggle to make the link. As the participants aged, they slowly began to be able to use their memory systems more efficiently with almost no sign of this ability in the youngest, sporadic use throughout adolescence, and robust use in fully developed adults.

Differences Between Teaching Older and Younger Students

Memory is often thought about as simply recalling events from the past, but this study shows that while any typically developing human brain can form and recall memories, the logic needed to link those memories together to make useful inferences is something that must be developed over time. Teachers already have a plethora of strategies to help students remember and recall information more quickly, but there is more that can be done to help students, young and old, develop their logical usage of their memories.

1: When teaching younger students, walk through connections explicitly.

Since younger students will struggle significantly to make sense of disconnected events, the teacher can verbally explain the logical connection to help the students to understand how a connection can be made. This can help students understand difficult situations as well as help them develop critical thinking skills.

For example, a young student may remember that previously they had been allowed to work with a partner and decide to speak to their friend about their work during a test. Even if the student has taken tests before, they may not be able to connect the memory of needing to be quiet and not talk with a partner during a test to their memory of just working with their partner in the previous activity. Because they aren’t good at connecting memories to make inferences, they may not understand why they aren’t being allowed to work with their partner due to only pulling from one memory.

Teachers can use these opportunities to walk students through why what they were doing was wrong in an educational tone rather than a reproachful tone. While the student may need a firm reminder, the teacher should always take the time to calmly and positively walk the student through the mistake and help them understand the logic in the teacher’s thinking.

While explaining in the moment can be useful to help the student make the connection immediately, sometimes, especially when frustrated, it may be better to have these conversations after a few minutes has passed for the emotions to be less strong. If the student is too upset, they won’t be able to activate their logic centers and the teacher’s attempts to help develop that area will fall on deaf ears.

2: Use logic building test questions for teaching older students.

As students age, teachers can find new ways to help students to develop their thinking and help them learn how to connect information in logical ways. Questions on a test or quiz tend to be completely separated from one another, just pulling individual memories together from what the student has been studying. For teenagers however, teachers could consider trying to leave context clues in their questions by layering them in a way that if they’ve answered previous questions and understood the implications, they will be able to answer following questions due to their logic.

This can be done most easily on multiple choice questions where the same answers are used multiple times in a row. For example, if questions 1-4 all have the same options for A, B, C, and D, students can remember that they’ve already used a term and be able to use the process of elimination to be better able to answer following questions or even correct mistakes as they realize they’ve gotten a previous answer wrong.

Other logical conclusions can be used as well such as if the answer to question 1: Who was the president of the United States in 1776 is George Washington, and the answer to question 2: When did the United States become a country is 1776, the student should easily be able to answer question 3: Who was the first president of the United States because they already know who was president in the first year the United States was a country and can use logic to infer that he was the first, even if not directly taught such.

Each subject will have its own logical pathways that teachers can use to help students think more critically, but often teachers don’t want to make tests “easy” because they want to challenge their students. Tests are just another tool to help students learn and shouldn’t just be made difficult for the sake of being difficult. There are ways to design and organize tests that help measure students progress at the same time as helping them to develop their brains and get more questions correct while learning more at the same time.

Want more like this? Make Lab to Class a part of your weekly professional development schedule by subscribing to updates below.

References

Schlichting, Margaret L., et al. “Developmental Differences in Memory Reactivation Relate to Encoding and Inference in the Human Brain.” Nature Human Behaviour, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01206-5.