Table of Contents

Teachers often struggle to find the balance on when to push their students to do their best, or give them a break to boost performance. When staring out into the faces of twenty blank eyed kids at 3:15 PM, how can the teacher differentiate boredom or disengagement from true cognitive fatigue? Recently, the mental health of students is more and more on the minds of teachers, but how can teachers decide when is a good time to give students a break and when they’re fine to keep moving forward?

Researchers studying Signal Detection Theory (SDT) recently completed a study in January showing a way to “objectively measure cognitive fatigue” (Wylie et al.) The research in this article will arm teachers with the neuroscience based research on when students really need a breather before diving back into course material and what to do when a break simply isn’t possible.

New Research on Measuring Cognitive Fatigue

Fatigue is what happens in the brain when attentional resources are stretched to their limits over a period of time and can often be caused by the brain having to do difficult tasks or multiple tasks simultaneously. As more is demanded of the brain, the brain struggles more and more to keep up with processing the information it receives properly and in a timely manner. When fatigue levels are too high, most learning is very limited and motivation will decrease due to feeling tired and overwhelmed.

Scientists have struggled to find a way to objectively measure how much fatigue the brain is experiencing at any one time, because unfortunately, people’s self reporting of their levels of fatigue is unreliable. Because of this, scientists have been searching for a more reliable way to find out how much fatigue a person is really experiencing. One measure that researchers have been looking into is connected to a concept called Signal Detection Theory.

SDT is a theory which helps neuroscientists describe how input from sensory information, like what people hear or see, is used in decision making when they are unsure of the decision they should make. (Wickens) Research done last year showed that “as subjects reported more cognitive fatigue, their perceptual certainty declined” meaning that as people became more fatigued, they were less certain about the information they received (Wylie et al., 2021)

However, despite subjects being fatigued, one surprising finding is that their accuracy didn’t correlate with that level of fatigue. Instead they found another measure far more reliable. They found that the subjects compensate for their fatigue “by requiring more evidence before releasing their responses” resulting in a longer time to respond, but not affecting accuracy (Wylie et al., 2021). In other words, rather than making more mistakes, people who experience fatigue will take longer to give their responses, because it takes longer to process information due to fatigue and therefore leads to feeling less confident to give answers.

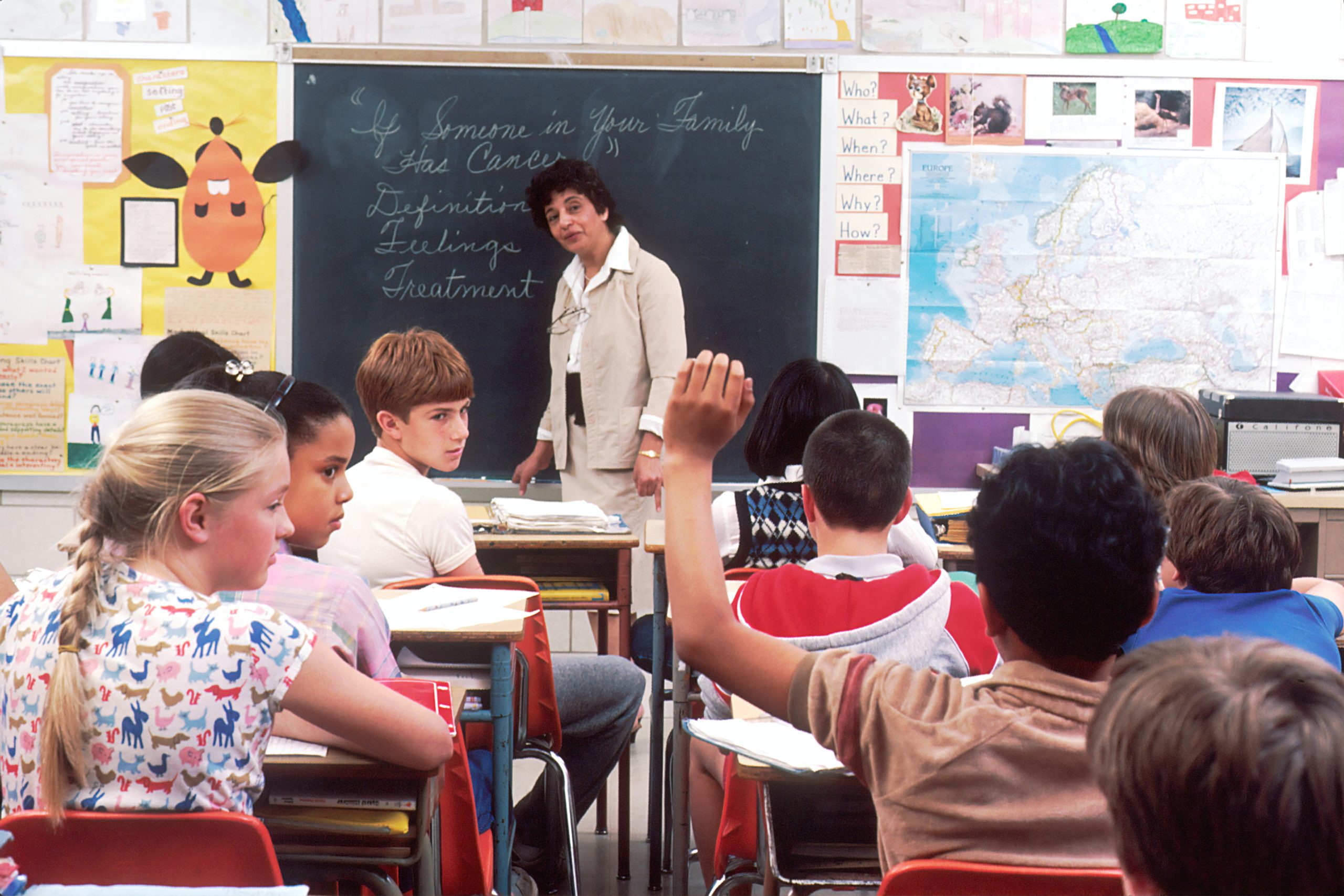

Recognizing Cognitive Fatigue in the Classroom

What does this mean for classroom teachers though? When students complain of fatigue, it can be difficult to know when they just need to be encouraged or pushed to better themselves and when the student really needs a break to be able to continue learning. When the brain is truly fatigued and their mental health is at risk, very little long term learning will happen resulting in teachers wasting their time and frustrating students. Students need to be alert and energized to be able to direct their attention and reinforce properly learned concepts for later recall.

With the research in mind on how cognitive fatigue leads to increased response time and lower confidence, one easy stop teachers should try is giving students a few very easy refresher questions and see if they still take longer to answer things they really should know already. If the students answer quickly and correctly, even if they seem disengaged or tired, this is probably not cognitive fatigue, and so the teacher can more confidently push the student or use strategies to re-engage without wasting time on a break. If, however, students take extra time to give simple answers, give totally wrong answers, or require extra prompts and hints for these low ball questions, it probably is a sign of actual cognitive fatigue.

Rather than continuing to do the normal lesson plan, this strategy allows the teacher to not only have a brief refresher on basics, but also really test whether students are mentally fatigued or just needing encouragement or pressure. In short, if students seem to fumble and give unsure answers to the easier questions given, take a five minute brain break and then the lesson can continue. If students respond quickly and confidently, the teacher can use this as encouragement for the students as they have gotten a correct answer and then received praise. Then the teacher can push forward confidently with the lesson.

Important Notes on Cognitive Fatigue

An important note is that cognitive fatigue levels can change! Just because a cognitive fatigue test is done at one point doesn’t mean students won’t become fatigued later in the lesson. Teachers must remain vigilant and aware of students and choose activities and questions that support their learning and prevent slowing of that learning due to fatigue or lack of engagement. Also, important for teachers to remember is that students often struggle with the fatigue of homework at home. Even after all of their classes, the work doesn’t end there, and now students are faced with more distractions than ever.

Students may become increasingly fatigued while working at home, but still turn in the same result to the teacher in class, making the increased efforts and struggle invisible to the teacher. This can lead to teachers not seeing the full impact of the work they assign which only manifests at a breaking point when a deadline is missed or a test is bombed.

Keeping a careful eye or even perhaps a brief log of students who seemed “off” in some way can help prevent not only fatigue, but also a host of other problems many teachers miss. There is no replacement for a teacher’s individual knowledge about their students’ mental health and the relationships they have crafted over the course of the year.

Research on Reducing Cognitive Fatigue

Sometimes however, some students may be slightly fatigued, but others are ready to learn. If the teacher was to take a mental health break, this might cause everyone who is still ready to learn to fall behind due to the limited amount of classroom time students have to learn everything expected during the year. Are there ways to fight fatigue other than just taking a break?

Another strategy proposed by the researchers was to increase the rewards associated with the task to engage participants and reduce their fatigue. “It has been repeatedly shown that changing the payoff matrix by increasing the reward subjects receive reduces fatigue” (Wylie et al.)

This payoff matrix being mentioned is the perceived cost by the brain of investing energy into a task. If the task seems difficult and mental resources are already strained, it is harder for the brain to value spending those resources on a task with only abstract rewards like “improving oneself” or “preparing for a test”. If other short term benefits are included, this can change the perceived cost/benefit analysis the brain is constantly performing and allow students to allocate more of their mental space to a task.

Fighting Cognitive Fatigue in the Classroom

Rather than trying to warn students of dangers if they don’t focus or threatening punishment, an alternative strategy for teachers is to add little rewards that students will value when time doesn’t permit a break. Something as simple as “whoever finishes all of their exercises before the end of class can use their phones” or “if we complete (difficult activity) today, we can do (activity students prefer) tomorrow” can help give that little boost to those students lagging behind.

To take this to the next level, teachers can gamify their classroom by having competitive rewards such as throwing pieces of candy to students who participate or answer questions correctly. This not only adds a little sweet benefit to their cost/benefit analysis, but also adds competition to see who can get the most. Whether it is the benefit of sugar, winning a competition, or getting a reward from the teacher, this strategy should help many types of students to give that bit of energy needed to finish out the day.

Of course, each student and classroom is different, so teachers need to remain aware of what works for their students and alter rewards based on who is tired and how fatigued the students truly are. More fatigue will require higher rewards to swing the cost/benefit ratio in learning’s favor and not just add to the cognitive load on their mental health.

Want more like this? Make Lab to Class a part of your weekly professional development schedule by subscribing to updates below.

References

Wickens, T., 2008. Elementary signal detection theory. New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

Wylie, G., Yao, B., Sandry, J. and DeLuca, J., 2021. Using Signal Detection Theory to Better Understand Cognitive Fatigue. Frontiers in Psychology, 11.