Imagine trying to cook a recipe from a cookbook without knowing what any of the ingredients look like, what any of the instructions mean, or ever having seen it made before. While some people are very good at following detailed written instructions and might be able to come up with something palatable, even the most ingenious chef would obviously benefit from watching an expert prepare the recipe before attempting to make the dish themselves. This is why creating effective examples is so important for students.

Being able to see examples of what the ingredients look like, how they should be used, and in what order, gives the chef’s brain a framework to think from when they go through these steps later as they make it themselves. This is especially useful for new cooks who still have a lot to learn.

They can note when they chop the ingredients larger than in the example and continue to dice. Or they can remember the color a dish is supposed to be from the example and when it is to be removed from the heat. These sensory clues are far more reliable than using words to describe the sensation. One person’s “golden brown” might be another’s “caramel brown.”

Going straight to the sensory experience itself bypasses language’s vagaries and uses a more reliable part of the brain. Additionally, because modern chefs get to see dishes being prepared, research into how the brain learns shows that they have a more solid framework for what they are going to do, what they want to follow exactly, and on what steps they might need to mindfully deviate. Effective examples break down all of the parts of the process to help the learner understand the various steps involved rather than just showing the finished product.

Students of all disciplines can benefit from using the power of effective examples before jumping into learning anything new. New research into memory and learning showed that when learning by example, the brain creates a “code book” of steps and actions which are then later utilized when performing the watched task. (Mou et al.) Teachers can use this knowledge to help make those steps and choices even clearer in their lessons and projects, therefore more efficiently utilizing this natural pathway for the brain to learn.

New Research on the Importance of Making Effective Examples

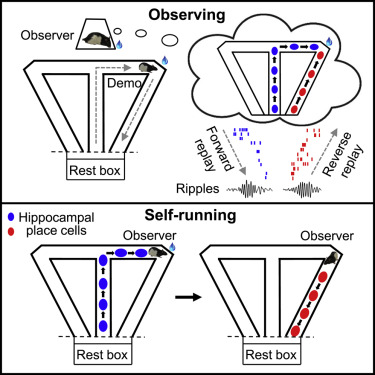

The study, published in Neuron, details a series of observations and tests that rats underwent while having their brains scanned. The rats started by watching another rat run a maze with a reward in it. While the rat observed the demonstrating rat, the researchers watched the brain of the observer carefully, noting a new memory pathway being created using special spatial memory neurons called hippocampal place cells.

Afterwards, the observer rat was given a turn to do the maze itself. Interestingly, the scientists noted that the rat used this same spatial pathway it had created earlier while watching the demonstrator rat to remember the steps of the maze and where the reward was hidden.

Rats who were allowed to see the maze and reward but weren’t given a social example had a harder time completing the maze and finding the reward because they weren’t able to create this same memory pathway that the rats who had an example had made in their brains.

The observer rat watched the “demonstrator’s spatial trajectory” and this formed the basis for their new spatial memory pathway. The researchers noted that the memories acted like a “code book” with choices the demonstrator rat had to make, where it made them, and which way it was went from that point. Rats without the example didn’t have any context when running the maze and so had to make choices on the fly, but rats who had seen another run it before had a basic understanding of what the maze was, what rewards awaited them, and how to reach them.

Making Effective Examples for Students

Any teacher who has tried to follow another teacher’s lesson plans will know that written explanations often fall short of giving full understanding on how something works in practice and don’t work as effective examples. While teachers unfortunately don’t have the time to leave visual demonstrations for their substitutes, they can use this visual learning pathway when making examples for student projects.

When giving instructions, teachers are careful to give clear written instructions as well as read them aloud while going over them with students. This is a good start as it activates multiple sensory pathways, the visual and the auditory, which gives the students more of a chance to remember the instructions correctly and for longer.

However, even students who think they understand the directions or ask questions will have misconceptions. Providing clear examples of what completed work looks like is useful, and definitely gives students an idea in their heads for what they need to do, but just giving completed examples has notable downsides. Especially with large projects, showing students completed work can be daunting and demoralizing.

While it might seem best practice to not begin a project without a completed example, the research from this study suggests that it might be useful class time to actually make example work in front of students. The teacher can demonstrate the various steps they take in preparing and brainstorming, discussing with students their thought process.

The teacher can just mindfully model the first step or whatever steps the students will be completing that day rather than jumping straight to a completed project. This way, students will have watched and collaborated in making the example themselves with the teachers guidance and then they can better understand how to repeat the steps with their project’s context.

What is nice about this approach is that it doesn’t just model how students are to do a single project, but it works to model how to approach learning in general as well. If teachers model approaches to learning in class rather than just discussing them, students will have a better set of strategies they can look back on to solve their own issues. The most effective examples are the ones that are made in front of students.

Teachers are also an important adult role model in a student’s life. Not just a giver of information, teachers can model how to handle difficult situations, how to stay resilient when things don’t go well, and help create more independent and confident students.

They can also show that it is okay to not have the answers to everything and model for students how to go about getting information they need when they hit a roadblock. This will be a boost to students who feel inadequate because they get something wrong or don’t know anything about a topic.

They will see that sometimes the teacher needs to look up a word too, and sometimes the teacher even has to erase their work. The teacher should be honest about their emotions, their frustrations, and help students see that these are natural emotions to experience as they go through difficult work. Therefore, modeling the creation of the example work not only serves as a code book of steps and instructions, but also works as a way to teach students how to problem solve and be more resilient in learning anything through this same modeling method.

Want more like this? Make Lab to Class a part of your weekly professional development schedule by subscribing to updates below.

References

Mou, Xiang et al. “Observational Learning Promotes Hippocampal Remote Awake Replay Toward Future Reward Locations”. Neuron, 2021. Elsevier BV, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2021.12.005.