Table of Contents

From preschool to graduate school, there are certain terms that students need to learn and understand to be successful. Vocabulary is a fundamental aspect of any course, and every teacher should be focused on teaching vocabulary better.

There are a multitude of ways to organize vocabulary words depending on the purpose of learning the terms and how they are to be used later on in the course. However, new research shows that many teachers make mistakes when teaching new words to their students.

On top of this, the research suggests that more mindful teaching of vocabulary can allow teachers of young students to catch language processing disorders more quickly. It is well known that the earlier a weakness in a student can be identified, the more effectively it can be targeted so that it has less of an impact on their learning later in life.

Teachers can use this research to not only teach using the most up to date practices, but also to watch for students who are not keeping up. After reading this article, teachers will have a simple and practical test to see how quickly students are developing the linguistic networks in their brains and understand which students will need an early intervention long before traditional testing will show anything.

This approach is eerily similar to a game everyone played as children…Any guesses? Keep reading to find out!

Research on Teaching Vocabulary Better

A study out of Purdue University found very interesting results on the development of lexico-semantic skills using eye tracking software on children learning new words. Their research was done on young children and sought to understand better how the development of these skills could be used to identify learning issues earlier in a child’s life.

What are lexico-semantic skills?

A lexicon is a set of words the person understands and can use, while semantics refers to words meaning in context. Children with high lexico-semantic skills have a large vocabulary and know how to use various words appropriately in different contexts.

In addition to simply understanding words and how to use them on their own, another aspect of lexico-semantic skills is the ability to understand how words are related to one another. Words can be more or less related to one another such as how “Monkey” and “Tiger” are more related as types of animals than “Monkey” and “Telephone”. There are many different ways words can be related, but it is important for children to understand these relationships in order to have strong lexico-semantic skills later in life.

Using Eye Tracking to Test Linguistic Ability in Children

The purpose of the study released just this month was to use eye tracking software to see how quickly children were able to understand these connections between words. Children were shown various sets of pictures and words were said to them based on the pictures shown.

“As we talk about something, we often look at it,” said the lead researcher, Arielle Borovsky. “We’re trying to learn not only about whether they’re understanding words, but how quickly are they understanding them? Do they understand that there are words connected to that particular word?” (Borovsky

The researchers found that the children who were quick to look at related images were better at understanding the relationships of the words. In addition to this, the children who were better at this activity showed higher linguistic abilities in a follow up study months later.

This study gives a clear way to test linguistic ability much earlier than traditional educational testing is able to. The earlier difficulties can be noticed, the quicker interventions can be put in place to help make sure that students don’t fall behind.

Teacher Takeaways on Teaching Vocabulary Better

While very few teachers will have access to eye tracking software, this study still provides several clear indications for how teachers should change their approaches to teaching vocabulary. These 3 simple tips will give teachers the resources and approaches for teaching vocabulary better.

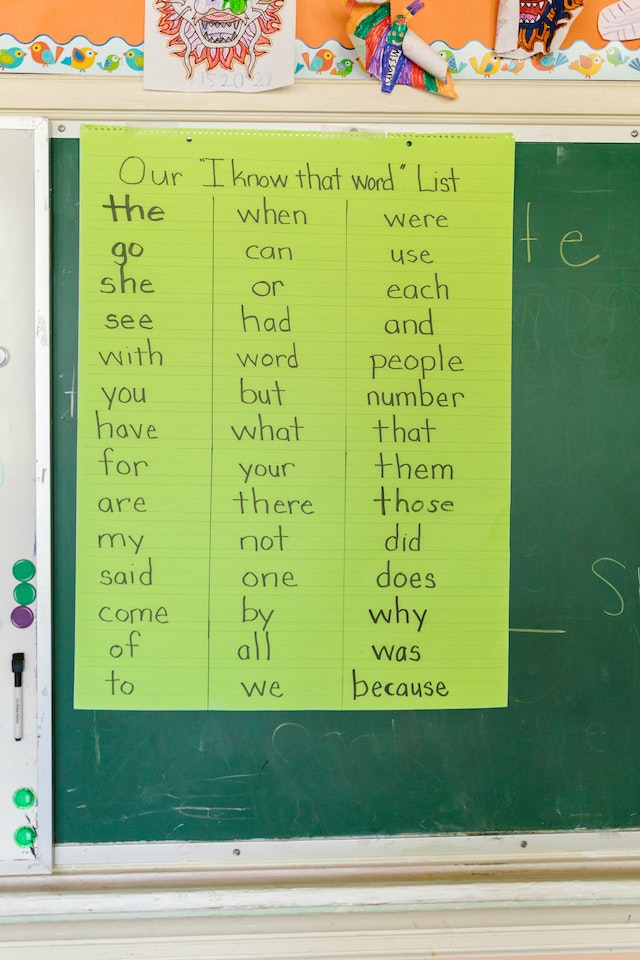

Group Vocabulary Conceptually

The researchers found that it was more important for linguistic development that children understand how words are related to one another rather than simply knowing a bunch of unrelated words. In the researcher’s words; “Denser semantic connectivity (i.e., global level connectivity between near and far neighbors) positively associated with semantic interference during semantically related lexical processing, whereas denser category structure (i.e., lower-level connectivity between near neighbors) facilitated lexical processing in semantically unrelated trials.” (Borovsky)

For teachers, this means that instead of focusing on cramming in as many vocab words as students can handle, they should focus on making mindful connections between a more moderate number of terms. This makes sense as having a deeper understanding of a few terms is more useful than simply knowing a vague definition and spelling of many terms.

“The findings support accounts that early vocabulary structure and lexical processing skills promote continued growth in language.” (Borovsky) If teachers focus on building students vocabulary structures and networks of understanding, students will be better able to learn vocabulary in the future.

So while it may temporarily lead to fewer vocabulary terms learned in a unit, in the end, students will have a better ability to learn new words that they can take with them long beyond the class and even graduation.

Before each unit, teachers should ensure that each of the terms they expect students to learn is actually covered in a meaningful way in the class activities. It is not an appropriate approach to simply pull every bold term from a textbook in a 21st century classroom.

This will ensure that students are not simply glossing over terms, but actually spending mindful time understanding concepts that they can put into practical use. To some teachers, this may seem like “dumbing down” content by expecting less of students, but in reality it is more of a “quality over quantity” argument. Students should still be held to a high standard, but the high standard should be in their depth of understanding of terms, not simply the number of terms they can recite and spell.

Make a Game Out of Teaching Vocabulary

The researchers in the study used photographs to gauge how quickly the children could understand the relationships between words through eye tracking software. Though most teachers will not have access to eye tracking software, there is a simple game most people have played that can give similar results as the study and help students to understand the relationship between words.

One of These Things is Not Like the Other is a common game played by children that requires them to understand which of four pictures is least related to the rest. In order to be able to play the game, children need to know what the four pictures represent and then decide what common relationship between the words one of the four words is missing.

For example, if a child sees a picture of an apple, a banana, a pear, and a firetruck, the child should circle the firetruck as it is not a food. While this is a simple example, the game can be as simple or as complex as the teacher wants. Variations of this game are even used in some IQ tests.

A science teacher could list out mitochondria, cell well, endoplasmic reticulum, and islets of Langerhans and see if students can figure out which of the four does not belong. Three of the four are parts of the inside working of a cell, while the islets of Langerhans are whole cells in the pancreas.

This way, not only do students need to understand what the terms are, but they also know the context in which they are important. With this method of studying vocabulary, students can also be asked to explain which term does not fit with the rest and why.

Social studies teachers could use a similar approach giving their students the terms Trickle Down economics, privatization, Universal Healthcare, and free market capitalism. This way, not only do students need to know the terms, but they also have to know which are conservative policies and which are liberal.

This approach to teaching vocabulary can be very advanced and allow for teachers to really test whether students know how concepts work together rather than simply parroting back a definition they memorized last night. This is not just useful for older kids, but can also be used for young students as well.

For example, the teacher could give her young class the set of words jump, eat, umbrella, and run. The students would have to understand that three of the words are verbs and umbrella is a noun.

Alternatively, this approach can be used to teach spelling conventions. Students could be shown the words chair, cheese, child, and choir and asked which does not fit based on sounds.

Another approach could be showing students a picture of a boat, a goat, a rope, and soap. Students could be tasked with spelling out the words to find out which of them does not fit the OA spelling pattern.

Start Interventions Early

The new research suggests that young students who struggle with these types of tasks may be more likely to have a language processing disorder. The earlier that learning difficulties can be identified, the sooner that appropriate interventions can be put into place and the better outcomes the students are likely to experience.

Teachers should always be on the lookout for students that seem to be struggling in any area. It can sometimes be difficult to tell why a student is falling behind their peers, but flagging students that seem to struggle with certain tasks is crucial to getting them the help they need.

If a teacher notices a problem area, they have a couple of options on how to proceed, depending on their school’s structure and learning support facilities. Bringing up a student to the learning support staff, a head teacher in your department, or even the school psychologist can all lead to beneficial conversations.

Each of these experts may have suggestions for how to help the student to improve and may have already heard about this student’s issues from other teachers. When one teacher brings up an issue, it does not necessarily lead to much action, but when multiple teachers repeatedly report similar issues, this can lead to the student being asked to go for an evaluation.

Even if nothing happens directly as a result of the issues brought up, if more teachers speak up in the future, administrators will be more likely to understand that it is a serious issue.

Alternatively, the teacher can first go to other teachers of the student. This can be teachers from previous years or teachers of other courses. They may have additional insights or suggestions that can be tried before going to a higher-up.

Either way, it is important to act sooner rather than later. If the teacher can put in differentiated supports and other scaffolding, the student may not need to go for a full neuroeducational evaluation, which can save the family thousands of dollars and get the student on the right path earlier.

Conclusion

While it is not always easy for students to learn the massive amount of vocabulary required from all of their classes, this study reveals one of the ways teachers can help to build up a student’s capacities from the ground up. Rather than simply trying to cram as many words in a student’s head as possible, teachers should focus on capacity building so that learned words are not simply forgotten as soon as that week’s vocabulary test has been written.

Using simple games like One of These Things is Not Like the Other, teachers can help to identify problems much earlier than traditional testing would be able to. This knowledge and approach to teaching vocabulary can help to nip linguistic issues in the bud before they bloom into true learning difficulties.

Want more like this? Make Lab to Class a part of your weekly professional development schedule by subscribing to updates below.

References

Borovsky, Arielle. “Lexico-Semantic Structure In Vocabulary And Its Links To Lexical Processing In Toddlerhood And Language Outcomes At Age Three.”. Developmental Psychology, vol 58, no. 4, 2022, pp. 607-630. American Psychological Association (APA), https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001291. Accessed 2 Oct 2022.