Table of Contents

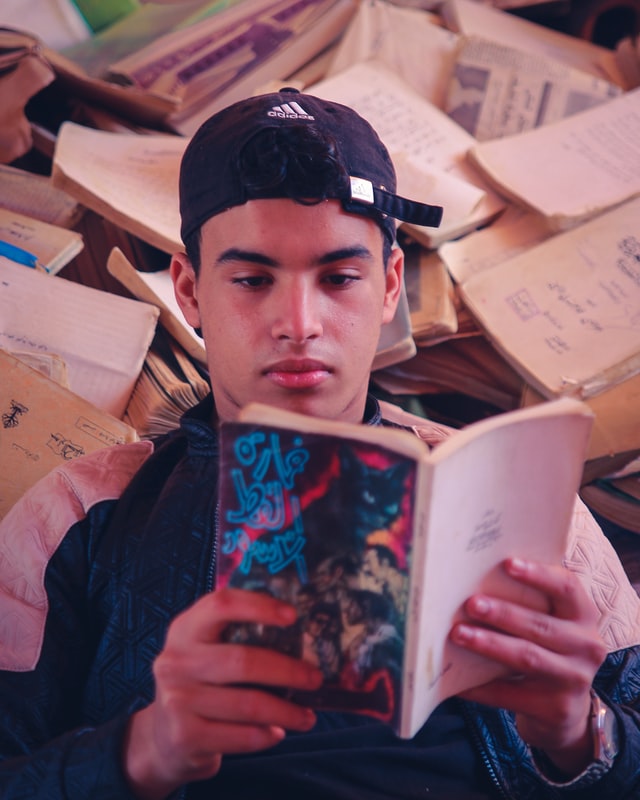

Dyslexia is often described as a disability as it can impact a person’s ability to read texts quickly and efficiently. People worry, because words such as “diagnosis” and “symptoms” are used when talking about dyslexia, that dyslexia is some sort of disease or developmental problem. What causes dyslexia, however, is actually a natural process and people with dyslexia can still learn to become effective readers despite their weakness in the area.

While dyslexia can certainly hinder a person’s ability to do well in the rigid rules of standard education, new research has shown that what causes dyslexia is simple evolutionary variation in our species much like any personality difference. Some people are better at sports than others, but there is no diagnosis required for clumsiness.

This article discusses recent research that has come out on dyslexia which may help to redefine how teachers and psychologists think about the condition. It focuses on explaining what causes dyslexia and what that means for teachers and students. For 5 easy ways to help your students with dyslexia, check out these easy to implement interventions.

What Does Dyslexia Mean?

The word dyslexia can be broken down into its two parts “dys” and “lexia”. “Dys” is a prefix meaning “bad” and “lexia” refers to reading. Dyslexia as a “diagnosis” simply means that a person scores lower than average on tests of reading ability.

There are no connections between dyslexia and general intelligence. A person with dyslexia may score below, at par with, or well above their peers in other domains. Dyslexia simply identifies a relative area of weakness in a person’s cognition.

How is Dyslexia Diagnosed?

Dyslexia has no single test or scan that can diagnose a person as having the condition. Instead, psychologists and psychiatrists may use several tests, questionnaires, and information about a child’s educational and family history in order to make a diagnosis.

There are many tests such as the CELF, the WISC, and the WIAT which all can give mental health experts information about the individual and may be used in part to give a dyslexia diagnosis. No one source can give a clear answer of whether a person has dyslexia and so if a diagnosis is given, it is based on multiple data sources along with the expert’s best judgment.

Types of Dyslexia

Dyslexia is not a single condition with a common source, but rather an explanation of a set of symptoms seen. This would be like a disease being described as “coughs a lot and has a fever”. This could have any number of sources such as a cold, flu, or infection. What causes dyslexia can therefore differ significantly in different people with the same diagnosis.

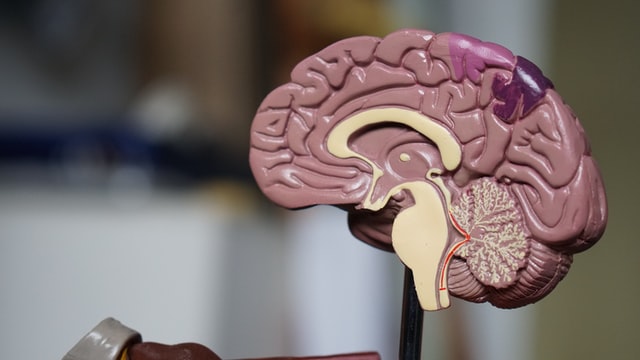

Similarly, the brains of people diagnosed with dyslexia all look significantly different. Though there are many common issues around reading among people with dyslexia, there is also significant variation in how and when those symptoms present. There are several subtypes of dyslexia currently being discussed.

- Phonological Dyslexia

This type of dyslexia is characterized by a struggle to connect letters to the sounds they make. People with this type of dyslexia struggle to sound out and learn new words due to struggling to connect letters and combinations of letters into the appropriate sounds.

- Surface Dyslexia

Surface dyslexia is a visual issue where reading is difficult due to visual processing issues. This is the type of dyslexia where words or letters can seem to move.

People with this type of dyslexia struggle to process words as a whole. They can sound out new words with ease, but struggle to read quickly as their brains have difficulty with processing whole words as a unit like most quick readers do.

- Double Deficit Dyslexia

Double Deficit Dyslexia is simply the combination of both the above phonological and visual issues causing reading difficulty. As a result of having issues from multiple sources, this is the most severe type of dyslexia and can cause major issues in school.

- Rapid Naming Deficit Dyslexia

Rapid Naming Deficit is a type of dyslexia that is more of a processing issue than a true dyslexia. Processing speed is often low in this type of individual and so not only will they process letters and sounds slower, but they will also struggle to name colors and numbers as well. However, because it also affects reading, it is often classified as a type of dyslexia.

Research on What Causes Dyslexia

Regardless of subtypes, there are many clear targeted interventions that can make a difference for students struggling to read. Research into dyslexia has shown that targeted interventions are often very successful in helping students with dyslexia to improve their reading fluency (Tressoldi, et al.)

Students with dyslexia should not have all of their work read to them or in audio format, because this will deprive them of the chance to improve their area of weakness. Rather than viewing students with dyslexia as disabled and incapable of improving, teachers should simply use a dyslexia diagnosis as a data point to help identify areas of weakness in a student.

All students have areas they are strong and areas where they are weak. That is the product of evolutionary variation in the brain. New research out of Cambridge University has shown that rather than dyslexia being a sign of delayed development, the brains of people with dyslexia simply have traded lower linguistic abilities for exploratory adaptability.

Brains can be broken into various functional regions like those that handle linguistic information or help in recognizing patterns. Despite all brains having the same basic regions, these regions are not all exactly the same in different individuals. This allows for significant variation in humans which improves evolutionary fitness.

Some areas may be slightly larger than average, taking over nearby regions usually inhabited by other functionalities. This leads to brains that can look and function significantly differently from one another and show that brain development is not simply a linear process, but highly individualized.

This effect is so pronounced that before brain surgery, the neurosurgeons have to map every individual’s brain using Intraoperative Brain Mapping in order to ensure they make incisions in the proper place. (Glasser, et al.) They will certainly have a general idea of where the borders of various regions should be, but the exact borders shift significantly in different individuals and therefore require careful mapping to make incisions in the appropriate locations and not damage functionality.

The Cambridge study showed that people who had a diagnosis of developmental dyslexia were more likely to display traits of learning through exploration rather than through reading or listening. The study broke people into two camps, those who have an “exploitative process” who learn by using what is at hand as efficiently as possible, and those who have an “explorative process” who learn by seeking out new things, ideas, and connections.

Learners with an exploitative process focus on learning by efficiently using tools already at hand. They learn by listening, reading, and working with systems. These types of learners are great at improving efficiency and not wasting time or energy.

However, learners with an explorative process focus much more on exploring creative solutions. They often are out of the box thinkers and can come up with solutions that exploitative process thinkers would never even consider. While some of their explorative learning may end up being inefficient or even wasteful, it is often these types of thinkers who make big changes.

The study highlights how people with dyslexia are oftentimes simply explorative process learners and simply struggle to learn in the way traditional education generally functions. Traditional education generally focuses on an exploitative process, asking students to use the textbooks, lectures, and other tools to pull out learning rather than creating new ideas themselves.

The research here may sound very familiar to the learning styles theory. This theory posits that there are many different types of approaches to learning and they all have their own strengths and weaknesses. The important thing is to not isolate different learning styles, but to help them build off of their strengths and bolster their weaknesses so that they can be adaptable in the ever changing world.

Conclusion

This study suggests that rather than being classified as a developmental disability, dyslexia should simply be considered a sign of a student having a specific learning style. What causes dyslexia is simply normal evolutionary variation. While this may make them less effective in a traditional school setting, this type of thinking has an evolutionary basis and has helped humans explore their environment, try new things, and make new discoveries.

While these learners may tend to learn best in an environment that is not completely reading focused, that does not mean that teachers should remove reading from these students. Students with dyslexia can absolutely improve in their areas of weakness just like any other student. They are not broken or incapable, simply different.

Instead, teachers should work to include a variety of tasks, lectures, and projects to challenge all students to improve in their areas of weakness and build on their strengths using the framework of Universal Design for Learning rather than Differentiation which divides students. Rather than focusing on each student’s differences and treating them differently, Universal Design understands that all humans have unique individual brains that have areas of weakness and areas of strength.

Want more like this? Make Lab to Class a part of your weekly professional development schedule by subscribing to updates below.

References

Glasser, Matthew F., et al. “A Multi-Modal Parcellation of Human Cerebral Cortex.” Nature, vol. 536, no. 7615, 2016, pp. 171–178., https://doi.org/10.1038/nature18933.

Tressoldi, Patrizio E., et al. “Efficacy of an Intervention to Improve Fluency in Children With Developmental Dyslexia in a Regular Orthography.” Journal of Learning Disabilities, vol. 40, no. 3, May 2007, pp. 203–209, doi:10.1177/00222194070400030201.