Table of Contents

What is Multisensory Learning?

Multisensory Learning is a well established theory of learning that states that brains learn information better when more sensory inputs are involved, especially the senses of sight, hearing, and touch. The theory focuses on the drawbacks of how students often learn in modern classrooms, merely abstractly discussing or reading about topics rather than experiencing them firsthand.

Almost every class in most formalized schools around the world, students spend the majority of class time learning about information in a way that requires language processing rather than sensory processing. Whether it is a novel in a literature class, a math worksheet, or a history lecture, students are only learning about topics through second hand explanations rather than first hand experience.

The Theory of Multisensory Learning in the Brain

On the surface, multisensory learning seems kind of like an alternate pathway in the brain to reach a desired destination or memory. If one pathway is blocked or has heavy traffic, having multiple routes allows for another option to get to the goal destination or memory. Different pathways may be more or less accessible at different times, and having multiple routes improves the possibility of being able to get to the destination in a timely manner.

However, on the neural level, a better comparison would be the way water would fill in a maze. Even if one pathway is blocked from one side, the water can flow around blocked pathways to flood the entire system.

In the brain, when a memory is activated, rather than only one sensory connection lighting up, once the initial activation of the memory has occurred, scientists also see activities in all of the previously connected experiences even when no corresponding stimulus was present. This is why even seeing a picture of cookies can conjure up the smell and taste of the warm delicious cookies despite no odor or flavor being present whatsoever.

According to neuroscientists who published a study on the neural basis of Multisensory Learning last year, “Associating multiple sensory cues with objects and experience is a fundamental brain process that improves object recognition and memory performance.” (Okray, et al) In other words, brains are built to remember objects better via sensory information.

Rather than multi sensory learning being simply multiple ways to remember something, it actually creates an entire mental experience for each memory connected with all of the sights, sounds, and smells associated with that concept. These mental experiences all work to reinforce each other, creating an ever stronger memory network to work from when applying their knowledge in the real world.

“This broadening of the engram improves memory performance after multisensory learning and permits a single sensory feature to retrieve the memory of the multimodal experience (Okray, et al) Because one little signal can turn on an entire memory experience, teachers really need to be capitalizing on this type of sensory memory whenever possible rather than storing memories only as linguistic information.

Why Multisensory Learning Matters for Students

Medical schools have long known that students need more than simple book knowledge to be effective doctors. While reading and lectures of course play a major part in medical school, any doctor could tell you that reading about a procedure is a lot different than performing it.

The same can be said for almost anything students learn in school as well. Employers often complain that their new hires directly from university lack many practical skills. Young adults also often complain that despite graduating with good grades from classes covering algebra and calculus, they are struggling with simple things like their taxes or understanding a mortgage rate.

This is because things often look a lot different in practice than they do in theory. Books can only attempt to conjure up appropriate images in students minds to give them a clear picture of what they are discussing.

However, when students listen or watch material that activates their visual and auditory centers directly, they can get an immediate understanding of what something looks and sounds like without having to spend time reading text intended to conjure up that image in the reader’s head. This allows for more time for the students to consider what they are seeing or listening to and for narration to focus on implications and connections rather than simple description.

Watching a video of someone performing a medical procedure is much faster than reading about the procedure in a book. In addition to this, while the student is watching the procedure, the video can include audio description of things the students should be thinking about or watching for. Because the warning is being said as the students are seeing or hearing the warning signs are occurring, a direct connection is being created between those warning signs and the issue itself.

Because the students will have created a direct connection between the visual cue along with what they are supposed to do, when that visual cue occurs later in real life, the brain will already have that pathway prepared and it will be easier to activate due to the memory trace that was previously created.

If the student had only read about those warning signs, when they see something concerning, they will have to mentally process those signs with the linguistic information they have learned to see if this is an actual instance of the described phenomenon or simply a misinterpretation.

While this may seem a bit abstract in the context of a medical situation, anyone who has tried to follow a recipe from a cookbook and then watched a video showing a recipe will immediately understand the benefits of multisensory learning. Cookbooks include linguistic terms that are very subjective and do not have firm definitions such as when they instruct the reader to whisk “vigorously” or wait until the cookies are a “golden brown”.

One person’s “vigorously” might be another person’s “firmly” or even “gently”. Similarly, one person might describe cookies as “golden brown” at a different hue than someone looking at the exact same batch of cookies in the exact same oven. However, when watching a cooking video, there can be no misinterpretation of these vague linguistic terms and the viewer can directly see the visual cues for how they are to prepare the ingredients.

In addition to this, the chef can give verbal instructions as they show the preparation methods to give warning signs such as “when you see it forming stiff peaks, stop whipping it”. This will directly connect the visual cue of “stiff peaks” to the warning to stop whipping and be more likely to prevent overwhipping than the person who only read the instructions in a book.

Multisensory Learning as Learning Support

Teachers who do not use multisensory learning approaches often do not have the flexibility to teach students with different learning needs and often have to rely on pull out models of education that take students out of their class to have teachers with more training handle the difficult case. Students with learning difficulties such as dyslexia and language processing difficulties benefit the most from the approaches of multisensory learning as it allows them to circumvent their areas of weakness and approach topics from ways of thinking that are more their strengths.

While multisensory learning is no magic bullet, giving students a variety of different learning materials that use different parts of the brain is guaranteed to have more students able to understand and grapple with the challenges the course has to offer. Even students without diagnosed learning difficulties have different learning styles and preferences, and while everyone needs to improve both their weaknesses and strengths, always having to approach course content in a way that does not come naturally to a person is absolutely mentally exhausting.

Examples of Multisensory Learning in the Classroom

For some subjects it can be quite easy to understand what multisensory learning looks like, but for others teachers might say that the topic is too abstract or completely linguistically bound. While some subjects may absolutely lend themselves more simply to a practical sensory context, really all subjects should eventually connect to a practical context the students will directly experience. Otherwise, why are we teaching it?

Literature

Literature teachers are often the first to suggest that their subject is not really possible to study through a multisensory approach. While they may grudgingly show some film adaptation at the end of a novel or play, it is a rare breed of literature teacher that finds ways to incorporate multisensory learning regularly into their classrooms.

While the initial reading of a text will inevitably need to be done through some linguistic means, teachers should be more open to the idea of reading aloud rather than always expecting students to read silently at home and come into class only to discuss. Reading aloud provides a plethora of benefits based on multisensory learning and also gives the teacher power to stop reading at any point and give students pointers or ask targeted comprehension questions.

In addition to this, while the text itself is technically always going to be linguistically bound, the teacher (or students!) can more directly connect the text to a real sensory context by giving animation to the characters voices and emotion to their phrases. Literature texts are often very abstract and it can be difficult to understand the emotions behind the subtle literary techniques some authors use, but if the teacher adds emotion and body language to their reading, students will be more likely to hear the words in a context that shows their visual systems the meaning and lets their auditory system hear the emotional cadence.

Film adaptations often cut important content and drastically change the author’s works to the point where it can feel shallow to look at them. A dramatic reading gets many of the benefits of watching a film adaptation while also ensuring students experience the true original text as it was intended to be experienced.

This is old news to any Shakespeare or other playwright fans, but other branches of literature need to stop looking down on audiobooks or reading in class as for preschool and learn to utilize this approach to give students the best possible experience of the literature as they can.

Another way literature classes can do more to bring the themes of their novels and plays alive is to ensure that they always connect ideas from stories to current events. Literature should not simply be a class about reading old books that snobby academics say are “classics”, but about teaching students important life lessons through the art of storytelling. If teachers can not think of a practical application for the novel they are reading, perhaps they should reconsider why they are teaching it to their students.

Language

Another group of classes that surprisingly struggle with being impractical and disconnected from multisensory learning are language classes. Despite having a clear and easily applicable practical context, many schools simply teach languages by having students do worksheets and mindlessly repeat vocabulary in classroom chants.

This is not how humans learn languages! Many people feel that adults are worse language learners than babies, but this is demonstrably false.

This is because of a fundamental misunderstanding about what actually constitutes “learning”. Babies spend 100% of their waking day experiencing their target language and using it to fulfill their needs and communicate their desires.

Adults go to class for an hour or write vocabulary words 100 times on a page and wonder how babies learn so “quickly” and “effortlessly”. The truth is that they don’t! Being young and learning your first language takes years of immersion and formal education in that language.

Adults who actually do the same process and fully immerse themselves in their target language learn significantly faster than babies. Babies require 5 years of language education before they are even ready for their first year at school! Adult learners can easily surpass this level in their first year of study even without fully immersing themselves at all.

According to the Foreign Research Institute, even the most difficult class of languages “ “Super-hard languages”, such as Arabic or Japanese, can be learned by the average adult in 88 weeks of full-time study.

This shows the power of multisensory learning in language learning. Teachers of language classes should be attempting to make their class as little like a classroom as possible and as much like other practical contexts as they can.

While some short grammar or vocabulary tips can certainly be helpful before an activity, the majority of class time should be actually using language in a practical context to communicate with their fellow students to complete a goal together.

Whether this is in the form of a game, a puzzle, a roleplay, or a discussion, teachers should realize that the more that they are talking, the less students are getting practice at using the language themselves. Lectures should be kept to a bare minimum and student participation should be the number one priority.

Many proponents of reforming language education suggest that students should go through a “second childhood” when learning a new language. Experiencing the world through exposure to increasingly difficult language in practical contexts to achieve simple everyday goals.

Countries like Japan and The United States have a reputation of having extremely poor language education despite being leaders in education in other areas. This is because the classes are often taught by teachers who barely speak the language and simply have their students complete worksheets and repeat vocabulary while the rest of the lesson is given in the students’ mother tongue.

In addition to keeping lessons practical, teachers should keep in mind the tips for difficult texts given for the literature teachers above. Just as adding emotion and body language to words while reading helps students to decode the meaning of words, teachers who clearly emote words they say help students to understand meanings of words through the principles of multisensory learning.

Students often mentally translate words in their head before understanding their meaning. This always adds an extra processing step as the brain must go from the word in the foreign language to the word in the mother tongue before being able to connect it to the concept to which it refers.

When teachers “show” rather than “tell” the meaning of words, students will not be as reliant on mental translation as they can see and hear the meaning of the word in the way the teacher expresses it. This will connect the visual and auditory clues speakers give with the meanings they want to express directly in students’ heads rather than them having to constantly mentally translate and then understand context clues after their brain has processed the linguistic information.

Social Studies

Social Studies is another subject many teachers struggle to know how to implement multisensory learning. While simple history texts themselves may have to be read or discussed in a linguistically bound way, the implications and reasons why studying history matter can very easily be shown, heard, and felt in very real contexts.

Reading about history can often feel like a bit of a pointless exercise for many students. Why does it matter that people know what a bunch of dead old men did hundreds or thousands of years ago?

Students are right to bring up this type of question. Many history courses are simply about learning a timeline of dates and the people and events connected to them.

Instead of organizing history chronologically, history should be taught thematically. For example, students could be taught a section about war and be given several examples of wars from the past to consider along with a current war where students can see pictures and videos of the ongoing destruction to see firsthand the ideas that are being discussed.

The examples can be looked at in a variety of ways from readings to video explanations to perhaps even history focused video games! This way students are getting a variety of different ways to experience and learn about the topic being studied and having their sensory impressions strengthened by visualizations and artist’s renderings.

In addition to this, history teachers should always ensure they are connecting their discussions to maps. Many students have a hard time visualizing the positions of cities, countries, and geographical features in their head, but by always having a map on display that the teacher can refer to, students will have a visual reference for where the events are occurring and how they might connect to events going on in neighboring areas.

Social studies may seem like a very linguistically bound subject, but by removing the unnecessary limitation of studying history chronologically, teachers will have a lot more freedom to use a variety of materials and examples to give students a clear picture of the lesson’s purpose. These rich visual materials can help history come alive and maps can help give students a concrete visual reference to organize the ideas they are learning based on where they occur.

STEM

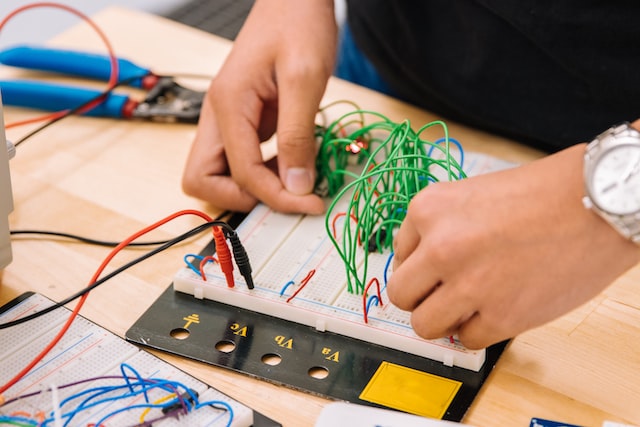

STEM classes have the benefit of being some of the easiest classes to put into a practical context and many teachers already understand the importance of practical applications. Many teachers in STEM classes require students to do many projects and presentations that require their students to show their understanding of math or science concepts in a practically useful context.

While many teachers are doing quite well, many others lack imagination when teaching their subjects and teach the majority of math and science concepts through formulas on a board rather than experiments, simulations, and projects. STEM teachers need to continue to fight to make their classes practically useful for their students and not focus on just teaching content for the sake of saying their high schoolers reach a certain level before inevitably forgetting it all less than 6 months later.

Rather than preparing students for standardized tests that they will take at the end of schooling, STEM courses need to ensure they are giving students practical skills that will immediately make them competitive in their future lives. In an ideal world, students would leave every level of education with a CV with more skills listed and a larger portfolio of work to prove their capabilities instead of just a piece of paper that says they could cram for a test.

Conclusion

Multisensory learning is not really a new concept, but new neuroscience research has helped teachers understand the importance of helping students to build full and clear mental models of the things they are learning rather than teaching them lists of simple facts that do not connect to a practical real world context. While some subjects are more suited to easy multisensory activities, all subjects need to do their best to connect their lessons with how students will utilize the information learned in their real life later on.

Just as the cook can better see what a recipe should look like as they are making it after watching a cooking video, this multisensory learning will help students to connect the lessons they’re learning from the novel, textbook, or worksheet with the time in their life that they will need to apply it. When they see the warning signs and experience the problems they have practiced in class, they will be better prepared to apply the lessons they learned in class rather than trying to figure out which piece of abstract information should be applied in their novel issue.

Teachers who teach using multisensory learning are also less likely to have students who struggle in their class due to a learning difference. Whether a student struggles with reading or language processing or not, multisensory approaches give students of all strengths something to latch onto and learn from.

While teachers can not revolutionize their entire curriculum overnight, they should absolutely start to add in more and more activities that implement the principles of multisensory learning. Each activity added will strengthen their students’ mental models and better prepare them for their future challenges.

Want more like this? Make Lab to Class a part of your weekly professional development schedule by subscribing to updates below.

References

“Foreign Language Training – United States Department of State.” U.S. Department of State, U.S. Department of State, 3 Nov. 2022, https://www.state.gov/foreign-language-training/.

Okray, Zeynep, et al. “Multisensory Learning Binds Modality-Specific Neurons into a Cross-Modal Memory Engram.” 2022, https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.08.499174.